Dorothy Iannone’s You Who Read Me With Passion Now Must Forever Be My Friends

What’s in a name? Take Douglas Sirk’s film Imitation of Life or Christina Stead’s novel For Love Alone—these are exemplary names, for they give precise definition to their objects, the works they denote. The American artist-writer Dorothy Iannone also takes names seriously, as the title of a recent collection of her work suggests. But the name here is more than a definition; it is a contract.

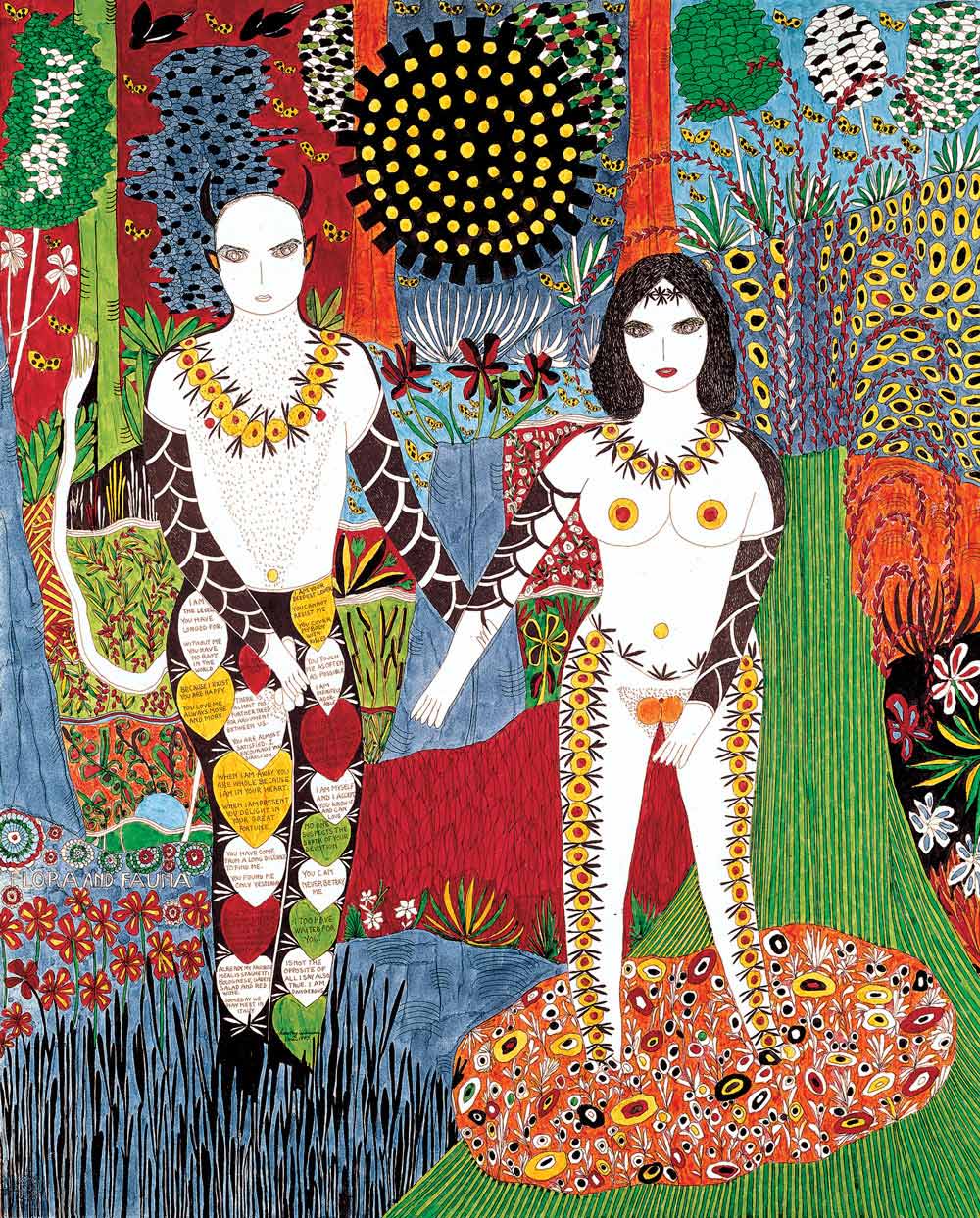

“Flora And Fauna,” 1973 by Dorothy Iannone, in You Who Read Me With Passion Now Must Forever Be My Friends, Siglio, 2014. Images courtesy of the artist and Air de Paris, Paris. Photo by Jochen Littkemann.

Born in 1933, Iannone had an ordinary charmed bohemian life until 1967 when, on holiday in Iceland with her husband, she met the artist Dieter Roth. Before day’s end Roth had asked to have sex with her, and she had responded by allowing him to gaze on her bare arse, an easy feat at the time, she writes, because she then never wore underpants. This was the 1960s. She continued refusing to make love with him for the entire trip. The day she returned to New York, she had the best sex she could have with her husband, told him she was leaving, packed her bags, and flew back to Iceland before the week was out. She and Roth then pursued an extremely passionate relationship until 1974, in Düsseldorf, Reykjavik, Basel, and London, while both made art, hers almost entirely about their relationship. Or so Dorothy presents the story in her work, an epic, ongoing auto-(erotic)-bio-graphic-al, all-painted, all-textual extravaganza, extracts of which have been handsomely bound by Siglio, the Los Angeles press specializing in image-text hybrids, with a focus on work by women.

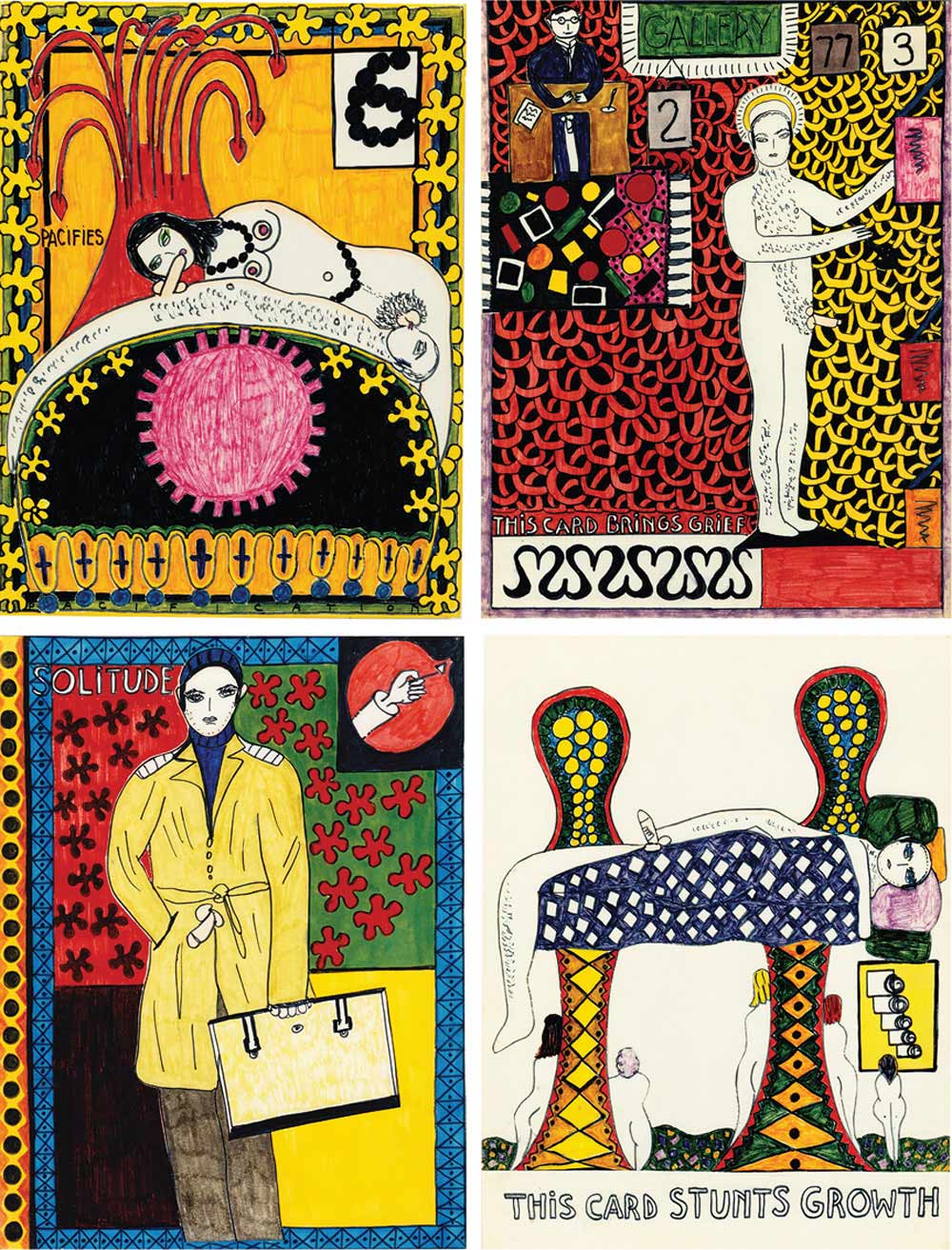

“(Ta)rot Pack,” 1968–1969 by Dorothy Iannone, in You Who Read Me With Passion Now Must Forever Be My Friends, Siglio, 2014.

Like many artists, Iannone is possessed by a scene that she cannot, nor does she wish to, stop repeating. In the typically titled “Pieces In Autumn, A Continuation Of That Cunningly Entitled Notes For An Autobiography, Part IV,” Iannone summarizes:

Long ago in that ephemeral paradise into which we are almost all born, while I was still vulnerably exalting in his beauty and in the abundance of my mother’s breasts, my father chose to fall ill and die.

I look for the sweetest of men with passionate perseverance and I find again in my best lovers his amazing reluctance to linger. I urge, they resist—or so it seems—for, in the world, projects take precedence over bliss.

Unlike her male companions, for Iannone bliss takes precedence over projects. Indeed, bliss takes precedence over everything, and in her relationship with Roth she found it temporarily. Her artwork—a completely entwined mix of image and text, fact and fantasy, decoration and reflection—is an homage to that state, and to the phenomena that produced it: her sexual unions with men. Though after the breakup with Roth, her “muse,” Iannone never again found such completeness, she continued to seek it through an ecstatic communion with her work. Like those medieval mystics who express their love of Love, aka God, by allowing It, in Its incarnation as Word, to come (literally), Dorothy Iannone subsumes her desire, and lets Love Itself come through her brush. In a landscape dominated by “concepts,” and the idea that femininity is reduced to an object when depicted iconically, Iannone’s work has for decades been either censored or ignored. Perhaps at last we can overcome these limitations, and revel in the glory that (still) is Dorothy.