Roadsides

He leaps to Africa, to a few words spoken to him in the southern Sudan nearly a half century ago. I’d got to Juba with a Czech journalist, he says, and we had four hundred more kilometers to Congo, our destination. We had a permission to travel there and this British colonial servant took that paper from us. I begged. Please I need that permission to go to the border. He looked at me and said, “I am the border.”

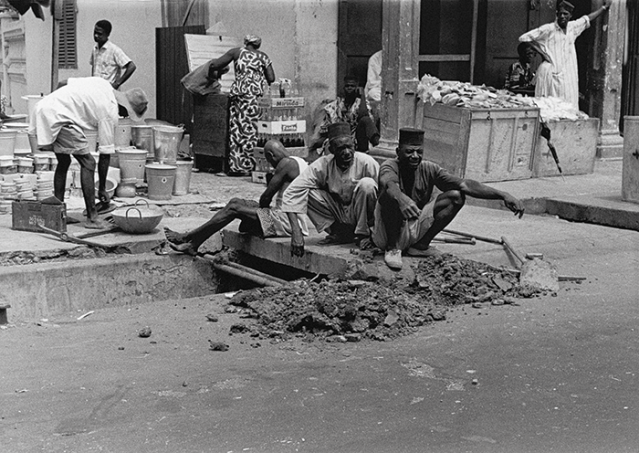

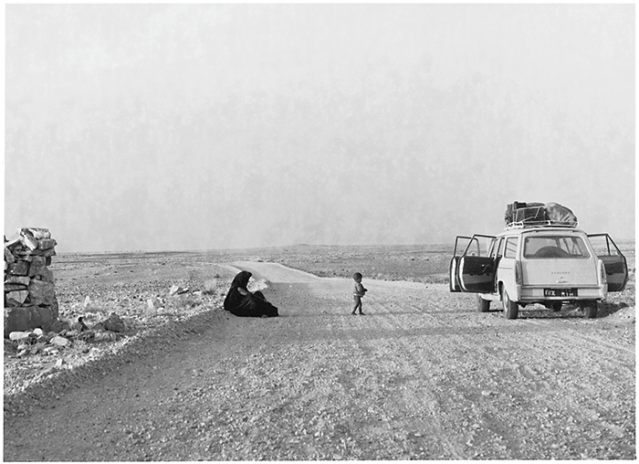

Along with his pen, Kapuscinski carried a camera where he went and kept for himself a record in pictures. The road was his element, so the film he shot is full or roadside visions like those in the following pages, taken during his many travels in Africa—a little boy clutching a scrap of cardboard; an overheated car on a Niger road; a torn-up street in Abidjan, Ivory Coast; child soldiers charging the camera.

In the winter of 2003, I made a plan with Ryscard Kapuscinski to begin a Paris Review interview. In the intervening years he and I kept trying to meet over a tape recorder in Warsaw, but the time was never right. In January, when I learned of his death, I discovered that I had jotted down a few notes from our only meeting, one night in a borrowed apartment in Greenwich Village. Here is what I salvaged:

Kapuscinski. First night. The room is uncluttered. A stopover. Like so many of the places he has inhabited in his life. He says he is working on several books—his travels with Herodotus; a history of Lvov, the Polish town where he grew up; and a collection of aphorisms. On the desk, a large notebook lies open to page forty. It’s blank. Two ballpoints and a red pencil that he uses to underline pages in Polish, are neatly placed on the desk along with George Seferis’s On Greek Style. That’s all. In the shelves are an assortment of books given to him—one on Greek travel, some Hemingway stories. Classical music plays on the radio. He perches on the edge of an ottoman, talking, gesticulating, and I sit on the couch barely a foot away from him. He has tiny feet. Strong arms. A narrow body with a small paunch like a little balloon. Two hours pass and we don’t move. Then he is on his feet, and a second later seated on the couch—half a foot away from me now. He goes on talking till midnight—no tea, no food, not even a glass of water. I’m going to faint. He’s so close I can see how parched his mouth is. His busy mind doesn’t care.

He leaps to Africa, to a few words spoken to him in the southern Sudan nearly a half century ago. I’d got to Juba with a Czech journalist, he says, and we had four hundred more kilometers to Congo, our destination. We had a permission to travel there and this British colonial servant took that paper from us. I begged. Please I need that permission to go to the border. He looked at me and said, “I am the border.”

And it was true, he says: after that man there was nothing. Until we got to the Congo and there I can see the image so clearly, a man and a woman completely naked. I ask, What was your greatest professional failure? He looks at me puzzled, embarrassed, and says, My life. I want to believe he means his life as opposed to his work. This is a solitary life, he tells me. Yes, I have a wife, children, but always I am alone. Loneliness is our constant companion, isn’t it? His eyes brighten warmly. Isn’t it? But it turns out that is not what he meant by failure. He actually meant his work. I’m never satisfied, he says. When I finish a book it’s not the book I meant or wanted to write. Well, give me an example, what book would you have liked to write differently or how? If I knew I would have written it. It’s just a feeling.

He recalls coming of age as a reporter under totalitarianism. He describes the changes that happen in the mind of the writer, the reporter, the newscaster, how the internal censor develops and introduces a new way of thinking that seeps into his reports. It happened with us, he says. It wasn’t overnight in 1946, it was a slow process. And the same could happen here. You’ll see, he says.

There’s a blank space in my notes as if I was trying to represent a memory lapse. Then comes one of the aphorisms he offered that night without context: The stupid man says all he knows. The clever man knows all he says. I’m dying for a glass of water. I can’t swallow anymore. I’m beginning to see double. He talks of vodka. I’d even take that. But no—the vodka he’s talking about is another history lesson. In the Soviet imperium, he says, vodka had its own moral code. You had to show up at a friend’s with a bottle. And once the bottle was opened, you had to finish it. And then, he says, one drank to prove one wasn’t a KGB agent.