Scale as Problem, Architecture as Trap

The following essay will appear in Climates: Architecture and the Planetary Imaginary, published this spring by the Avery Review and Lars Müller Publishers.

There is a strange sympathy between the atmospheric particles that float through the sky and the human beings who migrate across the ground and then across the sea. Each body sets the other into motion—a pattern of movement and countermovement. The particle bodies flow from north to south; the human bodies move from south to north. The difference in the kinds of bodies is apparent in the models used to grasp their character: on the one hand, there are the physical and chemical explanations used to model the climate system, and on the other hand there are the anthropological and psychological explanations used to model human character. Thus, the contact between human bodies and atmospheric bodies is the contact between these different kinds of models, the consequences of which are delineated in this story.

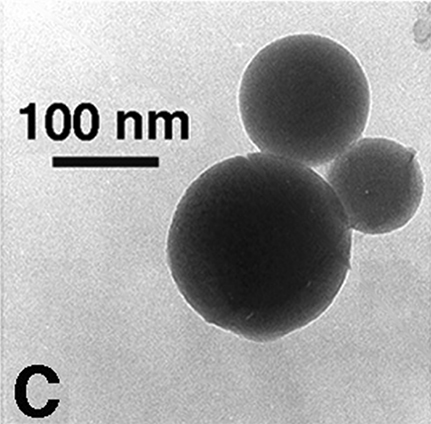

A carbon dioxide molecule under the microscope

Satellite imaging of human migration

The global climate model is actually a series of submodels that are refined until they capture the causal structure of the climatic problem to be reproduced. In climate modeling, as in other forms of simulation, the trick is to somehow reproduce enough information to catch what is relevant in a problem—no more, no less. A working model of causality is really just a reliable explanation of a problem that has been formalized. In terms of scale, this form of modeling operates like a mesh, the apertures of which must be tuned to catch elements of just the right size. Do you calibrate it to catch the weather pattern, the cloud formation, or the water droplet? It depends on what you want to explain. Scale is what organizes this objective relationship between the problem and the model.

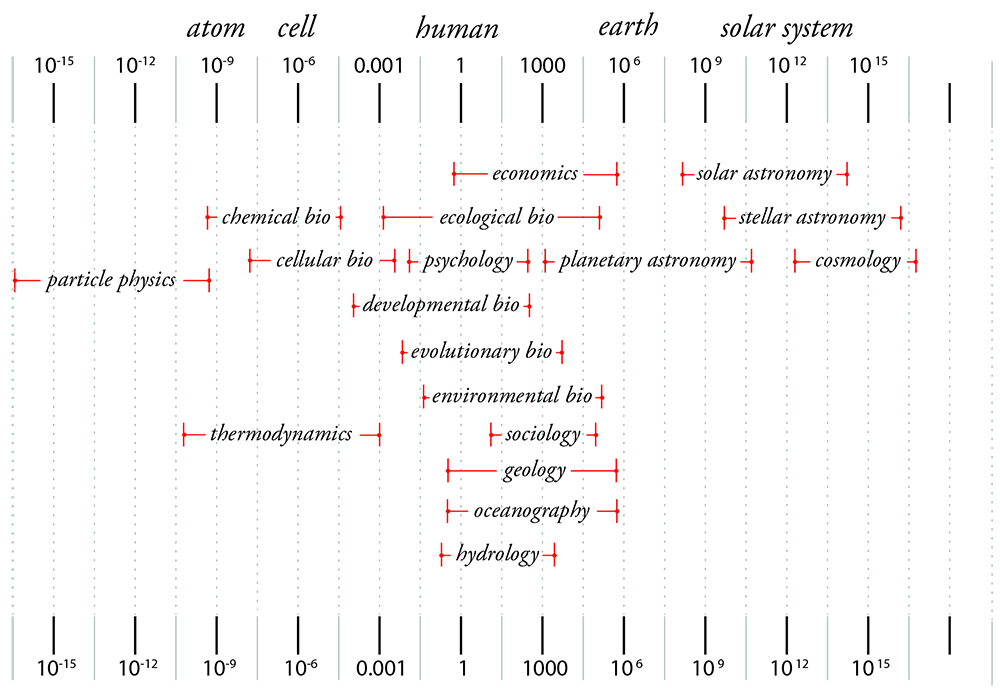

Histories of explanation and representation solidify around problems, meaning that we inherit conventions in knowledge production, perhaps none more important than the division of knowledge production itself into scalar categories. These categories emerge both as an objective reflection of the phenomena in question and the social, political, and economic decisions to orient scientific attention in one direction over another.

New kinds of problems—like climate change, for instance—pose special challenges insofar as they bring together the large and the small, the near and the far, the fast and the slow, the weak and the strong, making a mess of existing scalar conventions. The history of scale in climate science is an example. In the study of climate, signs must be extracted from a vast sea of scalar variability—this sea of cycles and oscillations span from a nanosecond quick flicker of infrared to the half-million-year passage of our astronomical seasons with all of the endless flux in between. Climate science has to extract individual rhythms from this cacophony. It has to work out what makes a rhythm, what makes it switch tempo, play more insistently, with more syncopation or just plain out of time.

Diagram illustrating scales of scientific inquiry, Adrian Lahoud, 2015

Scientists obviously set out to explain a wide range of problems through climate models. Even if the ground of verification differs, we find something similar when we look at models of human subjectivity. Here, the aim has always been to use the signs of external conduct to construct a model of internal motivation, to understand the way that conduct emerges out of natural dispositions—or, as Michael Feher has beautifully put it, according to a schema of conflict between good and bad propensities, such as charity and greed, passion and reason, shame and self-worth. Models of subjectivity are supposed to explain what causes human beings to behave the way they do. What happens, then, when environmental models intercept models of human character? How do social modeling and scientific modeling inflect each other? Examining changes across a band of arid land in central Africa may help to demonstrate the inextricability of social and scientific modeling, and the consequences of this encounter.

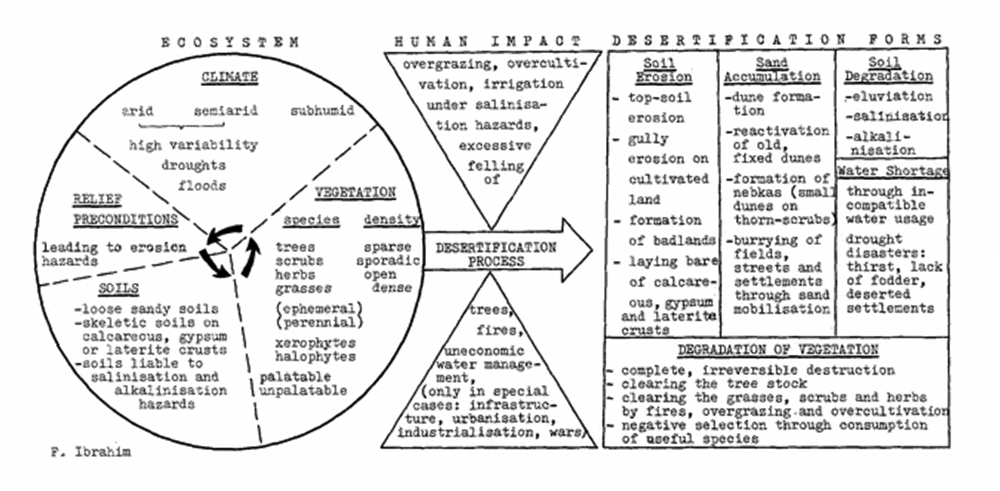

“Desertification” refers to the process by which arable land becomes unproductive, usually as a result of poor land management. For scientists like Jule Gregory Charney, the term became a kind of conceptual paradigm through which to understand the case of the Sahel and the severe drought that beset the region in the 1970s and 1980s. Essentially, what later became known as the Charney Hypothesis claimed that indigenous mismanagement of land was leading to a loss of soil and vegetation, and, more importantly, that this loss was changing the reflectivity of the earth’s surface, resulting in less rain. The account took hold of the Western scientific imagination; in their view the people of the Sahel had become weather-makers of the most self-destructive kind.

Desertification Schema from “Anthropogenic Causes of Desertification in Western Sudan,” Fouad Ibrahim, 1978.

The two kinds of models described above can be used to understand this account. First there is a generalizing and reductive explanation that attributes land degradation to the people’s character. The literature from the period refers to the farmers’ inability to reason, to plan, to calculate properly—that is, to their irrationality—but also to their inflexibility, to a lack of capacity to adapt their actions to changing circumstances. The other model of explanation involves the behavior of the environment in response to their actions: the irreversible damage to the earth’s surface triggered positive feedback in the atmosphere, which then caused drought. The intersection of these two models gives us a specific geopolitical paradigm: man-made desertification. The consequence of this paradigm was a disastrous legacy of ill-conceived aid packages, reforms, and interventions.

In the last decade, however, climate science has finally confirmed a saying of the Zaghawa people in Chad: The world dies from the north. The severity of the Sahelian drought made it a perfect object to train generations of climate models upon. What climate scientists finally deduced—counter to the prevailing narratives—was that the oceans were driving the drying of the Sahel. The first clue in this detective story was a set of models that correlated ocean temperature to precipitation, indicating that the heat in the ocean was acting like a pacemaker for the monsoon.

However, the relationship between heat and rain was still only part of the picture—something was missing. The models could reproduce the signal, but not its strength. Something else was driving the ocean temperature. Was it global warming? Answering this question was complex. What scientists found was that drying depended on a balance between two forces. The first was the temperature difference between cold and warm water in the tropics; the second was the temperature of the troposphere. Instability in the first would tend to more rain, while stability in the second would tend to more drying. The victor would drive precipitation patterns.

The balance of power was poised until an unlikely protagonist tipped the scales. As if in homage to Lucretius, fate would be decided by the infinitesimal swerve of a particle. Most people associate global warming with carbon dioxide. But fossil fuels produce another byproduct: aerosols. For some time science has been aware that European and American aerosol emissions were changing the temperature of the oceans. Scientists hypothesized that this was weakening the temperature gradient that was so crucial to precipitation patterns. Aerosol particles are unlike carbon dioxide in that carbon dioxide is long-lived and disperses evenly, which is why we can talk about parts per million as a global concentration. Aerosol particles are short-lived. They get lifted up in air currents, carried through the atmosphere, and then deposited. Their effects, therefore, are far more localized. Unlike carbon dioxide molecules, which are identical, every single aerosol particle is individual.

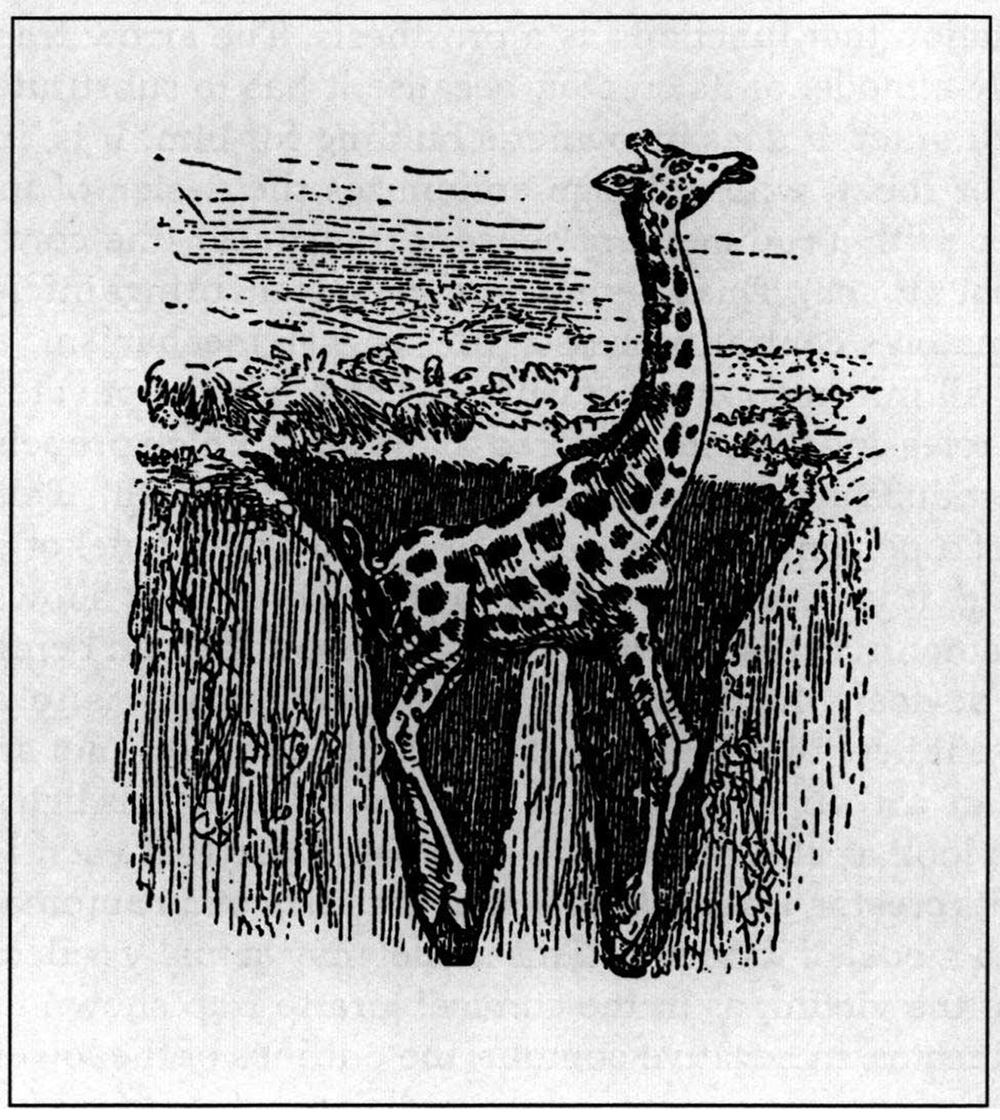

A Giraffe trap and a rat trap from “Vogel’s Net: Traps as Artworks, Artworks as Trap,” by Alfred Gell, 1996.

The trap rarely embodies the form of the prey, though sometimes it does, as in the humorous giraffe trap. More often, it embodies something essential in the prey’s character, such as the propensity of the rat to burrow. The trap expresses the ambition of the predator to catch the prey. Therefore, the trap is a designed object in which the character of the prey intersects with the intention of the predator. The chimpanzee trap, for example, solicits the natural curiosity and intelligence of primates. “The thread is very thin and the chimpanzee thinks it can get away,” recalls a member of Cameroon’s Fang community, Ze. “Instead of breaking the thread, instead of pulling the thread, it pulls on it very gently to see what will happen then. At that moment the bundle with the poisoned arrow falls down on it, because it has not run away like a stupid animal, like an antelope would.” The trap preys on the primate’s ability to balance its instinct with its intelligence. A small thread captures something essential in the character of its subject, better than an image.

The animal trap turns the personality of the animal against it. This is why Gell is right to think that traps always have a tragic dimension. If we train ourselves to look at architectural and environmental traps, we might be able to extract a portrait of the character of the prey or, more precisely, a portrait of the point of intersection at which the character of the prey and the intention of the predator meet. In architecture, power never touches the human directly. It addresses the human through the life world in which the human subject exists as a set of alternative, conflicting potentials. Environmental determinism would suggest a direct correspondence between climate or geography and the character of the human being, as if an unbroken line of causality chained the human character to the strength of the sun. But in environments, we never find lines of causality without fields of uncertainty. This uncertainty is not only what tempers the strength of our predictions or what qualifies the veracity of our claims. It is the terrain of political struggle itself. Architecture’s role in this struggle might be to contribute a particularly uncertain kind of trap, lacking in virtue and good faith, patient, malevolent, living and residing in our blind spots, the amoral, anti-Enlightenment object par excellence.