Echoes in memory, object and earth

An excerpt from the essay ‘Echoes in memory, object and earth’ by Dan Rule, published in the book ‘Belanglo’ (Perimeter Editions, 2015) by Warwick Baker.

Melbourne’s Perimeter Books is holding a one-day art book shop in our Hotel Hotel library on Saturday 16 July from 10AM to 5PM. Warwick will be there for a chat and to sign this new book.

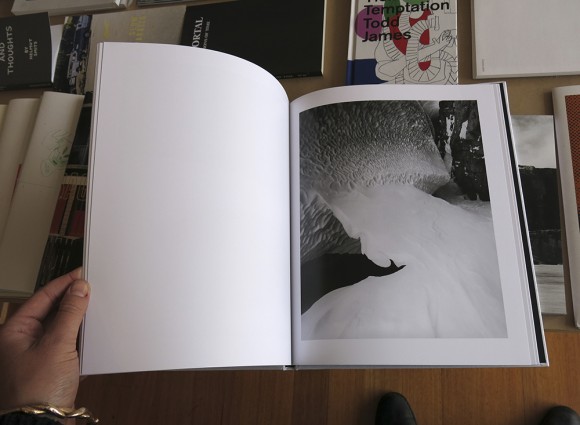

The Belanglo State Forest spans some 3800 hectares of undulating land amidst the Southern Highlands of New South Wales in south-eastern Australia. Set three kilometres to the west of the Hume Highway, around 90 minutes south of Sydney by car, the forest comprises vast plantations of radiata pines ringed by stretches of dense native bushland, rocky cliffs and valleys. It is a popular site for various recreational endeavours, and people from the nearby towns of Berrima, Moss Vale, Bowral and Mittagong use the forest for camping, hiking, trail bike riding and four-wheel driving…

The ground is uneven and rough underfoot. Dried leaves and twigs crackle with every step. A large branch lies slumped amidst knots of shrubs and stooped foliage. We make it to a small clearing that leads to one of the sites. A recently discarded Coke can has been left lying in the dust, uncrushed and perfectly formed. There is evidence of a campfire nearby – a crude arrangement of rocks and scattered fragments of charcoal half-buried in the dirt…

Writing on the ‘horror stretch’ – a notorious length of the Bruce Highway in the Central Queensland hinterland – in his book Seven Versions of an Australian Badland, Ross Gibson forwards the notion of landscape as “an ever-assembling mosaic of cultural artefacts, relics and stories that people have left on and in the ground”. To Gibson, the badland functions as an accumulation of geographical, historical, psychological and mythological constituents.

It is generative and self-fulfilling in its modes and mannerisms – “a paradoxically real and fantastic location where malevolence is simply there partly because it has long been imagined there”. The badland’s burden is an internal one. It disturbs us into identifying the histories that “we wish we could deny, ignore or forget”.

The Belanglo State Forest gained international notoriety as a result of the so-called ‘backpacker murders’ in the 1990s, considered one of Australia’s worst serial killings. In 1996, Ivan Milat, who lived in the outer southern Sydney suburb of Eagle Vale and whose family owned property near Belanglo, was convicted of the murders of seven young travellers, many of whom had been hitchhiking from Liverpool in Sydney’s western suburbs. He was sentenced to seven consecutive life sentences. The partially buried remains of Milat’s victims – who were of German, British and Australian descent – were discovered in heavy bushland within the Belanglo State Forest between 1992 and 1993. The horrific details of the case have been widely publicised throughout the Australian and international news media, and the Belanglo name has, for many, become irrevocably tied to notions of violence and trauma.

Boulders begin to interrupt the sandy earth as we walk deeper. The distant rumble of logging trucks can be heard. There are tyre tracks that come to a halt at the foot of a banksia, a short walk from the fire trail. A casing for a boxcutter blade lies nearby. The landscape becomes abstract, as if a throng of disparate signals. It is oddly, inexplicably tense.

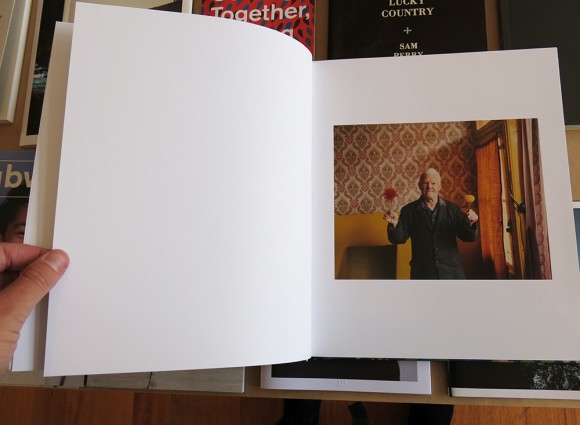

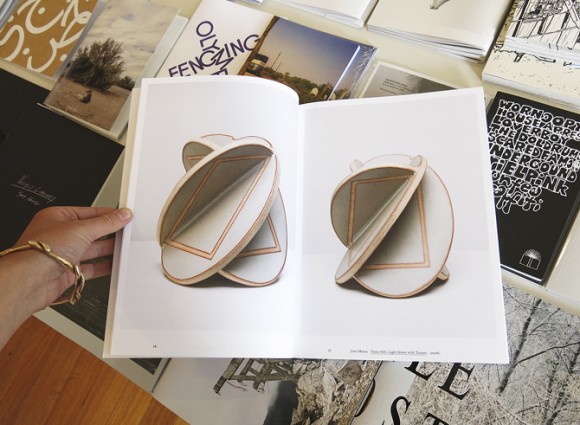

Warwick Baker’s photographs from in and around the Belanglo State Forest point towards our cultural and discursive deficiencies in dealing with the psychological, historical and emotional burden that such a space invokes. More than four years in the making, the project is a photographic meditation on sites of trauma and the psychological and historical resonances of landscape and place, whether imbedded, incurred, implied or imagined.

Baker’s use of aerial photographs, hand-held medium format images, large-format landscapes and still-life photographs imparts this body of work with a forensic, evidentiary and speculative tenor, making use of both traditional documentary techniques and a more lateral and experimental approach befitting the expanded conventions of the ‘new documentary’ movement. His work should also be considered for its engagement, reflection and rethinking of elements of the Australian Gothic, in both the genre’s historical and pop-cultural articulations…

But like much of Baker’s oeuvre – including his portraits, for which he has garnered significant acclaim – these images possess an extraordinary lightness of touch and sensitivity in their thematic wrangling. His perspective and approach to his subject sidles and subtly eschews a conventional photographic vantage and bearing. Recognisable iconography is of little interest, and his defiantly understated photographs elicit the double take. These are familiar images, made ever so faintly strange.