Object Therapy

A research

Remaking

Project

And

By

Hotel

Hotel

1. Foreword

Words by Dan Honey

Object Therapy is a research and remaking project by Hotel Hotel that encourages us to rethink our consumption patterns and re-evaluate the broken objects that surround us. It explores the almost forgotten role of repair in our society and its possibilities. Object Therapy is also an enquiry into humanity. The project examines why and how we load inanimate objects with meaning. The project has been developed in collaboration with the University of New South Wales (UNSW) and the Australian National University (ANU) for our Fix and Make program.Through a research-based approach it is an investigation into the culture of ‘transformative’ repair as practiced by local, interstate and international artists and designers.

In May 2016, through a call for submissions, members of the public submitted all kinds of broken and damaged objects for possible repair. From the 70 submissions, we chose 30 objects for repair including furniture items, ceramics, household appliances, textiles, sentimental objects and, unexpectedly, one human.

At the point of drop off the object owners were video interviewed by a team of researchers. They were asked a series of questions including how they came to acquire the object, how it broke and how they would like to see it repaired. In many cases these simple, straightforward questions drew out personal stories highlighting the power that objects have to connect us to people, places and the past. The video interviews also uncovered some attitudes towards repair and perceptions on waste.

The owners were then asked to ‘let go’ of their objects, understanding that the repair process might mean a complete transformation of the look and also the function of the object. Each object was then paired with a design repairer. The repairer was sent the object along with the video interview so that they could understand the owner’s relationship with the object. The repairers had six weeks to mend or transform the object. Once reunited with the object, owners were video interviewed a second time to record their response to the repair and to see how their attitudes or perceptions might have changed.

Object Therapy is a practical study of repair. It aims to build a new body of knowledge around repair, the design process, and objects and their meaning. Often, repaired objects are perceived as being of less value. Object Therapy seeks to challenge this preconception, celebrating repair as a creative process that can add value.

Excerpts of the video interviews with object owners can be viewed online at vimeo.com/channels/objecttherapy

If you have found this project interesting you might like to know that we are holding two talks as part of the project. They will bring the project designers and creative repairers together to discuss their contributions as well as the viability of transformative repair as a response to problems of obsolescence and waste in product design, and its potential as a service for users and consumers in need of options for repair.

Panel at UNSW, Sydney

With Benja Harney, Guy Keulemans, Andy Marks, Naomi Taplin and Trent Jansen.

Thu 20 Oct 2016

5.30PM for 6PM start

Panel at ANU, Canberra

With Susannah Bourke, Alison Jackson, Rohan Nicol, Monique van Nieuwland. Hosted by Niklavs Rubenis and Genevieve Jacobs.

Thu 27 Oct 2016

At 6PM

Tix

2. Objects

3. Essays

IN BRIEF: OBJECT THERAPY

Words by Guy Keulemans, Andy Marks, Niklavs Rubenis

The rationale for Object Therapy begins with simple observations: professional repair services are in decline, consumerism is rampant, and we are generating more and more waste. Do-It-Yourself repair is growing in popularity, evidenced by the growth of many excellent online communities and information portals, but this doesn’t cater to everyone.

We are consistently burdened by the untimely obsolescence of our possessions, and troubled by both our incapacity to discard them (to where?) and our inability to repair them (by whom?). Object Therapy is an attempt to answer these parenthetical questions and to highlight consumer perceptions of waste, repair and obsolescence. The project is an attempt to address some of the trouble caused by broken objects by connecting their owners with professional artists and designers. The skilled contributors we have assembled, the ‘repairers’, don’t necessarily have great familiarity with repair either. Some do. But they are all in command of considerable visual, material and technical expertise. Object Therapy intends to uncover, collate and assess the many and varied possibilities for creativity within the practice of repair. It was imagined that the generative aspects of damage, in which the conditions of wear, use and breakage can be unique, would lead to a broad range of creative responses and perhaps innovative repair typologies or techniques. As such, the brief was open. Repairers were provided with a video of an interview with their object’s owner and asked to respond in any manner they chose. We can identify these responses as having three main categories: transformative repair - a restoration of function with a change in form or appearance, adaptive reuse - a reconfiguration of material into a new purpose or function, and critical objects - that challenge the assumptions and conventions underlying the design, use or understanding of products. These categories are not a precise fit for all contribution and some outcomes merge or transcend them.

Transformation: the repairers and their repairs

Before we overview the work presented in this exhibition, firstly we should acknowledge that repair and reuse have historical roots within cultures across the world. The traditional Japanese craft of kintsugi – the repair of ceramics with urushi glue and gold dust – is an important precedent for Object Therapy. Its overarching concept, the aesthetic transformation of an object through a process of repair, neatly predicts the likely outcomes of merging visual arts and repair practice. We are lucky to include the work of master lacquer ware craftsman Yutaka Ohtaki in the exhibition whose repair of Lindy’s Western-style plate is unusual for traditional kintsugi. But as with the kintsugi repair of Korean and Chinese ceramics in the past, during the Edo period (1603–1868), it re- 5 territorialises the plate. Originally made in Europe, it now feels Japanese. Other contributors have worked in this theme. Naomi Taplin uses modern adhesives to sensitively repair a much-loved, ‘everyday’ bowl decorated with a fish. The golden seams diagram the force that broke it, subduing and ameliorating it. Conversely, Kyoko Hashimoto’s repair of Skye’s glass ring with a sterling silver sleeve recalls the time before the advent of modern adhesives, in which ceramics, in Chinese and Western traditions were repaired with metal staples. Traditional techniques deployed in the service of unconventional mending is evident in Elise Cakebread’s kilt repair, Liam Mugavin’s rocking horse, and Guy Keulemans’ use of photoluminescent pigments to craft a prosthetic leg for a broken glass giraffe.

Embarking on a different journey, Halie Rubenis’ playful decoration of chipped crockery with plastic spheres, fashioned from the expanded polystyrene box in which they were delivered to her, might not be fully functional, but the results are clearly transformational and revitalise everyday objects that are routinely discarded. Halie’s approach embodies that often referenced Australian ‘make do’ attitude of repairing with materials at hand. We see this in Andrea Bandoni’s repair of a clothesbasket with bright blue hose interweaved through the wicker. As a Brazilian, she cites ‘gambiarra’ culture, her country’s own version of the ‘make do’ concept.

Henry Wilson’s transformed bee smoker, a traditional tool used to calm bees prior to extracting honey from their hive, also leverages the ‘make do’ concept, but in the form of a critical object. After disassembling the leather joinery of the bellows, Henry was struck by the difficulty of finding replacement materials in inner city Sydney, an area similar to those in many Australian cities that have seen a decline in local manufacturing. Henry’s choice to replace the bellows with a computer fan - sourced from a computer supply store in the CBD – is a provocative hack that responds to the hurdles placed in the way of Australian makers and repairers, particularly when attempting to source local materials. It is the nature of critical commentary to find and dig out problematic roots. We might have expected Rohan Nicol to restore Kristie’s Kenwood mixer to function, given it’s sentimental history and potential for continued use. But, as Rohan notes, the mixer had lost its function sometime ago, yet hung around in disrepair. Rohan sees it as an abstract marker for the family’s inability to let go of their possessions. His transformation, a burial in cement, creates an ‘archaeological witness’ to the potential for grief in consumerism. In his repair of Chris’s inherited broken statuette clock, Rohan takes a similar path by binding the broken parts in cloth suggestive of ancient artefacts. He comments that the memory surrounding the object outweighs the object itself, enabling a moment in time to let the physical object go. The sentimental values within Rachel’s father’s bagpipes, harken to a Scottish homeland, and are unexpectedly reconfigured by Dylan Martorell. His hybrid instrument uncovers the traces and links between divergent global music cultures.

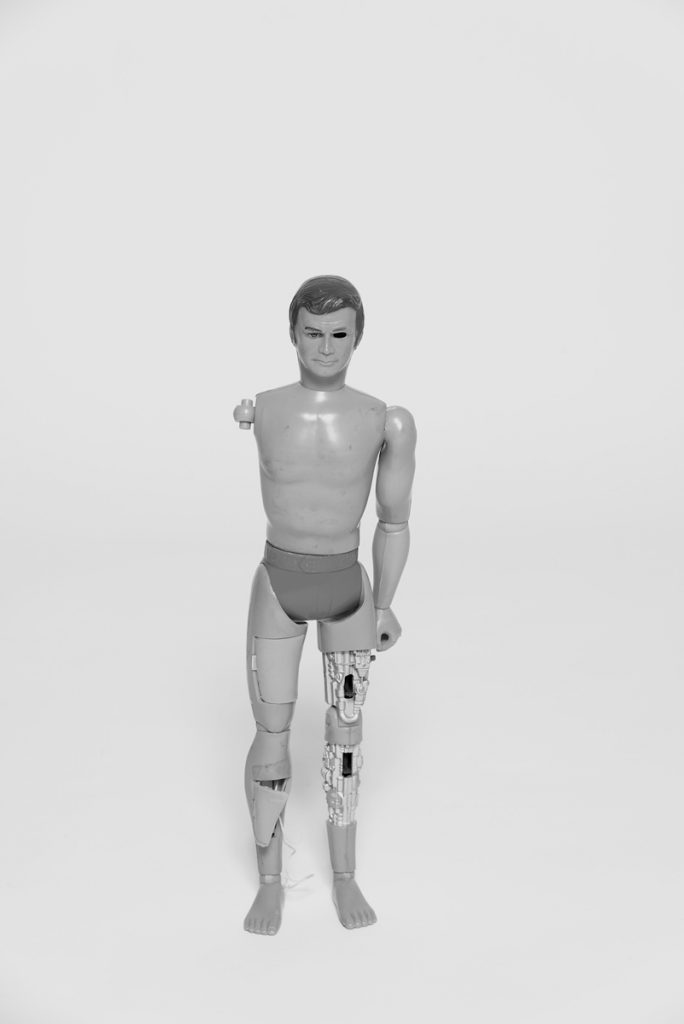

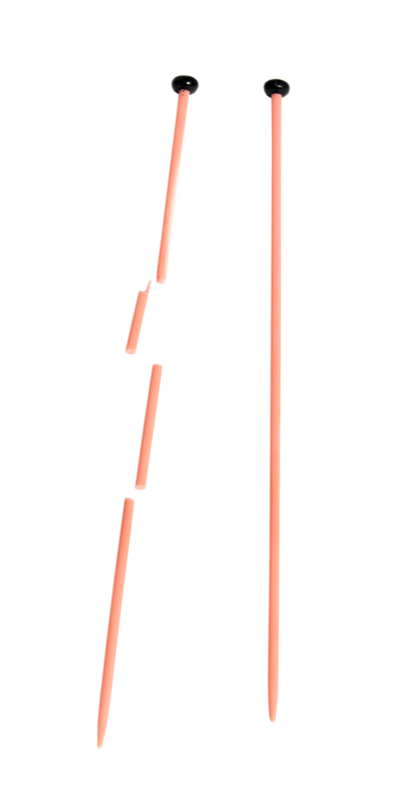

Appropriately, there is a therapeutic quality in many such contributions. It is seen in Kyoko Hashimoto and Guy Keulemans’ adaptive reuse of a cheap and broken, but incredibly precious knitting needle; in Corr Blimey’s sensitive transformation of a mother’s vintage kimono into a cushion for the daughter; in Elbowrkshp’s thoughtful deconstruction of a father’s Gladstone bag into three separate bags for each of his daughters; and in Scott Mitchell’s conversion of a beloved, obsolete television into a transmitter of televisual memories. Rohan’s ‘Six Million Dollar Man’ action figure – similar to one he owned as a kid – has been dressed in 6 detailed and intricate garments and accessories by paper engineer Benja Harney. Although only purchased from an op-shop for one dollar, this repair brings its cost into the thousands. This is not exceptional among our repairers, and we would like to acknowledge and deeply thank them for placing many hours of time and significant amounts of energy and resources into their repairs. This extraordinary investment is all the more remarkable considering the repairers make no claim to ownership for their work: the works will be returned to their original owners at the end of the exhibition. This incredible generosity fits well with the spirit of repair as a process that restores life to objects.

We thought we might test the boundaries of authorship in transformative repair by giving a broken vase, made by notable glass artists Ben Edols and Kathy Elliot, to another notable glass artist, Richard Whiteley. As former studio mates, though, this potential authorship issue was simply resolved by a phone call. More significantly, Richard’s repair, a clean slice that cuts away and discards broken edges and exposes a sublime interior void, has an unexpected therapeutic dimension. The vase was originally a wedding gift from a dear friend, since died. The cutting away of fracture is a material intervention into the complex emotional relations embedded by such provenance. It is an approach shared by Dale Hardiman’s knife repair. The knife’s broken edge, associated by the owner with divorce and death, was removed and its blade shortened. Its handle was replaced with a new one made from local clay, and the fragility of this material acts as a reminder to take care of our possessions, and perhaps human relationships as well.

Object Therapy has been full of surprises none more so than Peter who submitted himself as an object for transformative repair. Unable to envision what this might mean for research or exhibition, but unable to decline its possibilities, we passed his submission to Amsterdam-based conceptual designers Thought Collider. Their response firstly makes clear it is inappropriate to apply repair to a person as one would to an object, but nonetheless proposes a transformative experience through the form of collaborative research. ‘Peter the Person’, as he came to be known, has embraced their proposal to research colonisation of the moon in the public space of the exhibition. We hope his extra-planetary research might return attention to the grave problems of the earth and it’s human habitation.

Social and environmental problems were predicted to emerge from the Object Therapy process. Susannah Bourke’s critical object captures one of broad significance: the responsibility of companies towards the products they make. For her Mistral fan, this was an historical, life-taking lapse in electrical safety standards, but deeper and more nuanced problems of product design persist in affecting our contemporary world. We hoped to include more industry in our process, but Kenwood (now owned by Delonghi) and Nintendo didn’t respond to our invitations. Numark, a maker of DJ equipment, seemed initially interested, but soon went dark. We can only speculate as to the disinterest of industry, but note that there is an emerging and global community push for better corporate stewardship of consumer products. Such policy would require companies to take responsibility for retrieving, repairing or recycling their products from the post consumer landscape, but it is generally not the companies themselves behind these proposals. In absence of Numark’s participation, a DJ mixer got pulled from the Object Therapy process, but we can at least acknowledge the second hand electronics market (thanks Ebay) for helping us fix that owner’s other object, a retro Nintendo Gamecube. This fix, however, may be short lived, as those coloured RCA cable inputs connecting Gamecube to screen are disappearing from new televisions.

Problems of durability and obsolescence, the lack of lifecycle design and materials that harm the environment, are explored in many Object Therapy works. Trent Jansen’s transformation of an old washing basket trolley into clothes pegs is neatly conceptual, yet also interrogates changing material culture. Traditionally pegs were made from wood, but are now often made from petrochemical polymer plastics. The ‘new’ steel pegs made from the trolley’s frame look and feel like artefacts of a lost material culture. A light coating of rust is forming on their surface. Even if plain steel might be unsuitable for clothes pegs, they raise the question: in the rush to make everything faster, lighter and cheaper, do we lose or gain by switching to plastics from endlessly recyclable, but energy intensive, materials like steel?

Such questions are at the forefront for UNSW’s Centre for Sustainable Materials Research and Technology. They have developed patents for feeding worn car tyres into steel production and they specialise in extracting energy from polymer composites. In their contribution to Object Therapy, they brutally pulverised an unwanted stone giraffe for the purpose of material analysis, and followed this by turning its debris into a reconstructed polymer building product. This clarifies that varied techniques, both passionate and dispassionate, are required to tackle our tremendous contemporary problems of waste and consumerism.

The transformational capacity of material is also a concern for Niklavs Rubenis in his reconfiguration of 1950s furniture designed by Australia’s iconic Fred Ward. A deconstructed cabinet glides through a chair frame, forming a bench seat. Such adaptive reuse is not just transformative expression, but also transient expression, in that it opens up to the potential for further future transformation. This is also seen in Monique van Nieuwland’s reconfigured spinning jenny, now a wall-mounted clothes and hat rack; and Alison Jackson’s renewal of a child’s ruler, broken in play, into a set of playable dominoes. Subhadra’s submission, an expensive educational puzzle missing several parts, was a conundrum. It was impossible for her students to complete the task, but difficult to discard due to its cost. Daniel Emma’s transformation creates an entirely new game via a recontextualising face-lift.

Not all attempted repairs were successful. Richard’s theodolite, an instrument used for surveying, was prohibitively costly to repair. But it’s past use in mapping indigenous archaeological sites suggested an alternative approach. It has been given a political voice by Franchesca Cubillo in a text that calls for Indigenous sovereignty and respect for the wisdom of ancient cultures.

The sums: where to from here?

Object Therapy indicates the value and potential of repair as a practice by creative professionals. It highlights the positive concern that people have for finding solutions to product obsolescence and waste. We hope it may re-orientate attitudes towards production, consumption and disposal. This project draws attention to work yet to be done: Object Therapy is neither a comprehensive mapping of the possibilities of transformative repair nor a finished project. It is simply a starting point. Object Therapy points to the social and political agency required to transform the conventions of production and consumption, but, more importantly, we hope it points to a revitalisation of creative practice, skills and modes of thinking that will enable us to deal with the problems of the material here and now.

THERAPEUEIN

Words by Eleni Kalantidou

Therapy derives from the ancient Greek word ‘therapeuein’ and its meaning is strongly attached to curing, healing and bringing someone back to good health. Its original connotations as found in Homer’s ‘Odyssey’, Plato’s ‘Republic’, and Socrates’ ‘Apology’ reveal interpretations, not necessarily connected to mental or physical wellbeing. A case in point, Socrates’ understanding of ‘therapeuein’ was related to ‘taking care of’ and ‘looking after’ oneself (Foucault 2011, p.112) while in the ‘Republic’ (Plato, 2003) it was situated within a political milieu where it signified a responsibility for the common good, for people and their fate. What therapy means today is not greatly removed from the concept of care, the need to restore that which has been lost. Consequently, therapy becomes a form of repair, of getting back attributes that faded away. Making someone ‘functional’ again, allowing them to resurface via a new identity or giving them a new life through a new purpose mirrors discussions about broken objects. The only difference is that the inanimate and the animate become distinct by the fact that it is easier to define what ‘broke’ the former than the latter.

Object Therapy keeps these lines unclear; the object and the subject become one and are interwoven in the same story. Care is revealed and healing is pursued by sharing and letting go. Damage is negotiated through guilt, memories and effortless confessions; catharsis is achieved through knowing that the story (and object) will change. Emotions are in flux – nostalgia, attachment, grief, joy, responsibility. The separation from the object was in some cases covertly hard due to its ‘sentimental value’, a phrase often mentioned in the interviews. In his attempt to philosophically define it, Anthony Hatzimoysis identified ‘disuse’ as a common characteristic of things of sentimental value; ‘a broken ivory comb, a faded school tie, a collection of scratched vinyl records, are objects that fail to serve their designated purpose. Their sentimental value is connected with the fact that they are artefacts out of circulation’ (Hatzimoysis 2003, p. 376). In consequence, their uniqueness lies in being in limbo, situated between the past and the present and their effectiveness in triggering emotions of all sorts.

Considering that the attachment is mostly related to a memory evoked but not generated by the object invites an exploration of how the object became so precious. Most of the contributors were not focused on their object’s utility; they have either replaced it or just want to have it around as a reminder of a person or a moment. But the attachment is still there, as an indicator of the role that the inanimate plays in everyday life, as an inseparable piece of our artificial existence. What is repair then? Is it a means to instrumentally bring back to life an object that we need? Or a way to keep alive an object that we can’t live without? It is obviously not a question associated with survival. Or is it? The task was directly and indirectly linked to sustainment through the designers’ approach; they strived to save the object, its emotional value, its potential reuse, its monumental significance. Some of the objects can be reused, few retain their initial function, others have been transformed into playful reminders of the previous state of the broken artefact. Through their process of recovery they have opened up the potential of shifting the sentimental bond between the owner and the object to something unexpected. How the revived object will be experienced is yet to be discovered. In that manner, catharsis can be relieving or painful. Attachment may become stronger or disappear.

‘Finishing the job’ does not mean that the epilogue of the project will be written by the designers, the exhibition and the return of the object revived back to its owner. The vase, the statue clock, the television, the spinning wheel, the ‘broken’ man, the knife are all part of a narrative celebrating praxis, where ‘the end and the activity that produces it are inseparable, because the activity’s purpose is the activity per se and not its result‘ (Kalantidou 2015, p.96). In the event that the process does not have a telos, an end goal, the object will continue being redesigned by its environment and its interaction with its beholder and in a similar manner redesign them. The expectation is for this mediation and the pause created by the disconnection from the artefact and the subsequent catharsis to break the circle of attachment, to open up a new beginning where the emotional impact of materiality gets reduced to a stimulus and not the focus of the experience. Be that as it may, the research plan, the participants and designers’ engagement, the process of repair and re-imagination, have undeniably produced tangible proof that mending begins with confronting our-mediated by thingsrelationship with our self, our micro and macro-world.

References

Foucault, M., Davidson, A.I. and Burchell, G. 2012. The Courage of Truth: The

Government of Self and Others II; Lectures at the Collège de France, 1983-1984.

London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hatzimoysis, A. 2003. Sentimental value. The Philosophical Quarterly, 53(212),

pp.373-379.

Kalantidou, E. 2015. ‘Praxis’ in C. Edwards (ed.) Encyclopedia of Design. London:

Bloomsbury, pp. 95-7.

Plato, The Republic, trans. D. Lee. London: Penguin Classics.

4. Supported

Object Therapy is a Hotel Hotel project curated by Guy Keulemans, Andy Marks, Niklavs Rubenis and Dan Honey.

Project designers

Guy Keulemans

Andy Marks

Research investigators

Guy Keulemans

Andy Marks

Niklavs Rubenis

Photography

Lee Grant

Exhibition design, catalogue and website

U-P

Additional text

Eleni Kalantidou

Object Therapy is part of Hotel Hotel’s Fix and Make program. Fix and Make is a series of workshops and talks on how to fix and make things. Through the practical, the experimental and the philosophical, the program brings different people together to actively question our consumption of and relationship with objects.

Hotel Hotel is a hotel in Canberra, Australia. A place of collaborative craftsmanship made by artists, makers, designers and fantasists. Physically Hotel Hotel is a place made by and informed by art and culture. It is also a vessel for ongoing cultural and artistic creation.

Fix and Make is supported by

This project was assisted by a grant from Arts NSW, an agency of the New South Wales Government and supported by the Visual Arts and Craft Strategy, an initiative of the Australian State and Territory Governments. The program is administered by the National Association for the Visual Arts (NAVA).

Object Therapy was developed in collaboration with the University of NSW (UNSW) and the Australian National University (ANU).

ISBN-13978-0-7334-3668-0

Barry has lots to say about his television. Purchased by his parents in 1977, it was one of the first TVs manufactured for colour transmission; it had a remote control and was set-up for a video connection (something that Barry couldn’t comprehend at the time of purchase). The ‘tele’ was the dominant feature of his parents’ lounge room and he saw it as an object that brought the family together. Each night the family would sit in their respective chair with their dinner in their lap and enjoy the evening programs together. Barry was a latchkey child, and reminisces about afternoons alone in the house in front of the TV with shows like ‘Mister Ed’ and ‘Twilight Zone’ sparking his imagination. The TV had a series of levers on the front, one for contrast, one for brightness and one for colour. He recalls many arguments over the colour. Is it too pink? Is it too blue? In the early 2000s Barry moved the TV out to his back shed, not because it was broken but because it had become obsolete – a remnant of the defunct analogue broadcast system. He covered it in plastic and put the legs on bricks to prevent damage from the damp. Scott Mitchell has transformed Barry’s TV from a receiver of free-to-air transmission into a transmitter that echoes back electrical signals from an earlier time, repopulating the analogue airwaves once more, albeit on a very local level. Any screen that still supports analogue reception may tune into this transmission and experience Australian TV as it was in 1977. The original TV control panel is functional – here the channel selection can be made, and the volume and colour adjusted. Barry’s video interviews can be viewed here.