1. They did what human beings looking for freedom, throughout history, have often done. They left.

Stories

Stories

What we are thinking about,people we’ve met,what we’re up to.

By Date / A-Z

Raw like sushi… Or the story of the misunderstood brutes of concrete architecture

(Architecture)

We made a short film, ‘Brutti ma Buoni’, with Coco and Maximilian and U-P that premiered in Melbourne to a live score performed by Speak Percussion at Assemble Papers and Open House Melbourne’s Brutalist Block Party on Friday 20 May, 2016.

Research story written by Honey Fingers.

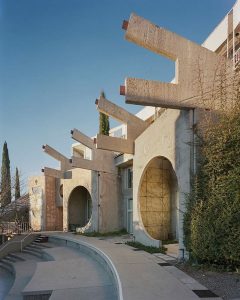

(1 of 2) The National Gallery of Australia shot by Will Neill

We were sitting on the shores of Canberra’s Lake Burley Griffin. It was a typical Canberra day: cool, bright, clear. A stiff on-shore breeze whipped up little whitecaps that lapped against the jetty below us. Aspen Island floated out there, on the other side of the lake, and above its little wood of poplar and willow trees the National Carillon (Cameron, Chisholm and Nicol, 1970) pointed forever skywards. I was nerding on about how cool it was – a concrete-block monument to tuned percussion; 55 brass-cast bells ranging from seven kilos to six tonnes, housed in a bell tower stretching 50 metres tall (daydreams of Arvo Pärt compositions raining down on my picnic blanket and so on).

She lit a cigarette and, after a moment, asked me if I thought the Carillon was a brutalist building. Good question. At the time I mumbled something about it being more an example of late-modernist monumentalism (whatever that is), so the question hung out there for me – somewhere between the little waves on the lake and all those bells; unresolved. I’m going to have a crack at answering that question now.

Brutalism – raw ideas lost in translation

But firstly, some definitions. In English we associate the term brute (Middle French brut, from Latin brūtus – ‘dull, stupid, insensible’) with the tough guy – a monster, a thug. Brutus kills Caesar, Brutus socks one to Popeye the Sailor Man. Brutal behavior is considered rough and savage, cruel and uncivilised. It is no surprise then that the honest and uncompromising use of concrete as a building material, brutalism, has fostered negative associations with buildings that, in the eyes of some, lack a certain humanity, are institutional in scale and often associated with (frequently failed) heroic social projects: mid-20th century English social-housing; abandoned communist bus stops in Eastern Europe; poorly maintained and insensitively renovated University dormitories.

The genesis of the term, béton brut, is credited to French architectural master Le Corbusier. He used it to describe his own material preference for projects such as the iconic apartment block Unité d’Habitation (1952) in Marseille, France. Béton brut translates not to ‘dull, stupid and insensible’ architecture but rather to ‘raw concrete’. The term was picked up in English and other languages, kept its French root, and incorporated into the moniker ‘brutalism’ by architects the likes of the Swiss Hans Asplund (who coined nybrutalism, or new brutalism, in the late 1940s) and thinkers such as Reyner Banham (who used it extensively in the late 1960s).

It’s funny to think about what was not only lost in translation – this idea of rawness – but what was also accidentally gained: the deadweight baggage of its English language associations. Imagine how we might think of this movement differently if, for example, the term that slipped into the mainstream of modern English was ‘rawism’, not brutalism. Raw like expertly prepared sushi; raw like superfoods; raw like bold new ideas. Associated with fresh theories about the honesty and purity of good, raw materials – not some thug-life architecture.

Raw power

Brutalism, although often associated with English architects the likes of Alison and Peter Smithson (22 June 1928 – 14 August 1993 and 18 September 1923 – 3 March 2003), came to describe a broad movement across decades, countries and political landscapes. And, like so many loaded design terms, there are debates about definitions and the works to be included, or not, in the oeuvre. For the purposes of this brief lake-side story, let’s define brutalism as a series of buildings, built between the 1950s and 1970s, that were often large and imposing (or had that vibe, even if they were small to medium in scale); were often made of exposed concrete, concrete blocks and ‘unfinished’ materials; and had a sense of raw, heavy sobriety about them. They were often, but not always, public or institutional buildings: social housing, universities, government buildings, public art galleries. But the private sector got a look-in too – there are many fancy brutalist hotels and business towers out there.

Contrary to its bully-boy reputation, it was an architectural movement underpinned by some very noble ideas and good intentions. Brutalism was a serious, if misunderstood, giant of a child seeded by the early 20th century modernist movement. And, much like its parents, was similarly concerned with the development of modernist themes: challenging the assumptions of its predecessors (including modernism itself); the use of mass-produced, cheap materials; was forward looking and caught up in all sorts of heroic ideas of progress and an ambitious, social crusade. These ideas translated well into the socialist architecture of Eastern Europe and social housing projects of free-market western Europe. The egalitarian and unpretentious use of humble concrete – as well as its relatively straightforward, scalable and cost-efficient building process – was a welcome development in rebuilding post-war Europe. But examples can be seen on all populated continents.

There was also an aesthetic pleasure in seeing various textures on the concrete walls: air bubbles, expansion joints, even the wood grain of the formwork. The buildings spoke about their own construction methods and architects often played with this to achieve decorative effects. The simplicity of a raw material used in this way was a fresh counterpoint to both the ornamental, historicist architecture of the 19th century and early 20th century as well as the haughtiness of high modernism. Le Corbusier was right – raw was cool.

So brutalism was appreciated for its aesthetics too and for this reason pops up in nice hotels and those temples of free-market consumerism: American shopping malls (about as far away as you can get from European social housing).

Brutalism’s bad rap has, in many ways, come from the association of the poor being clustered in concrete ghettos as well as the various misfires of socialist modernism. We have learned that even the best and most influential architects cannot solve intergenerational poverty, wealth inequality and other social ills via the design of buildings alone. Architects do not manage social policy or the budgets required to maintain these buildings. And concrete requires maintenance to address leaks and the associated concrete cancer. These big buildings also develop a patina over time – especially in the cool, damp climates of Europe. This natural aging process; a process that tells the story of season after season, is not appreciated by all. For many, a weathered facade is a failed facade. For some the sheer scale and wear and tear of these projects rates a poor one star on their eye candy chart.

In recent years, however, a new appreciation of these gentle giants of 20th century architecture has emerged. The architecture of the 20th century is, in heritage terms, a poor cousin to the often lauded and frequently heritage-listed examples of buildings built up until and including the 19th century. This is especially true in the Australian context. So today we choose to rethink and appreciate brutalism – a raw architecture that tells a story about the honesty of materials, of social design, of bold experimentation in architectural form.

Our test case – the National Carillon

So, back to my favourite bell tower, the National Carillon – is it a brutalist building? Its finish – white quartz chips in white concrete – is a little bit fancy. Raw? I’d say medium rare. It is also remarkably graceful and polite for a big, concrete tower – not in keeping with the brooding heavyweight atmosphere of its brutal siblings. It was a gift from the British Government to the people of Australia to celebrate 50 years of the national capital and free concerts are often played there for the people… So that does tick a few social boxes. Its privileged site on a bespoke island has all sorts of overtones of manicured public prosperity, old Empire and establishment however… For me it is a long way removed from the heroic efforts of brutalism to redefine, for example, social housing in the heart of the Empire, London. I love the thing, I really do, and file it right next to brutalism (its big toe definitely crosses the line into brutalist territory) – but, by this test, it’s not a truly brutal being.

And then there are the gum trees…

When she finished her cigarette we wandered over to the National Gallery of Australia (Colin Madigan and Andrew Andersons, 1970). As we crossed the air bridge that connects the foreshore to the gallery – with its bulky, rough-cast concrete balustrade and simple steel handrail – I stopped for a moment and took it all in. We stood on this bridge high among the trees: the smell of gum leaves trailing over the handrail; the familiar harsh chatter of white and pink parrots just up there, in the canopy; the angular masses of raw concrete, streaked here and there by decades of welcome rains and the soft hues of eucalyptus tannins. I thought to myself: now this is brutalism – and Australian brutalism at that. The weeping habit of a eucalyptus; those grey, mottled trunks; a single crescent-shaped gum leaf – they just look so good against a raw concrete palette.

Some misunderstood beasts

Cameron Offices, Canberra (John Andrews, 1976)

Plumbers and Gasfitters Employees Union Building, Melbourne (Graeme Gunn, 1971)

Robin Hood Gardens, London (Alison and Peter Smithson, 1972)

The Economist Building, London (Alison and Peter Smithson, 1964)

Western City Gate, Belgrade (Mihajlo Mitrović, 1980)

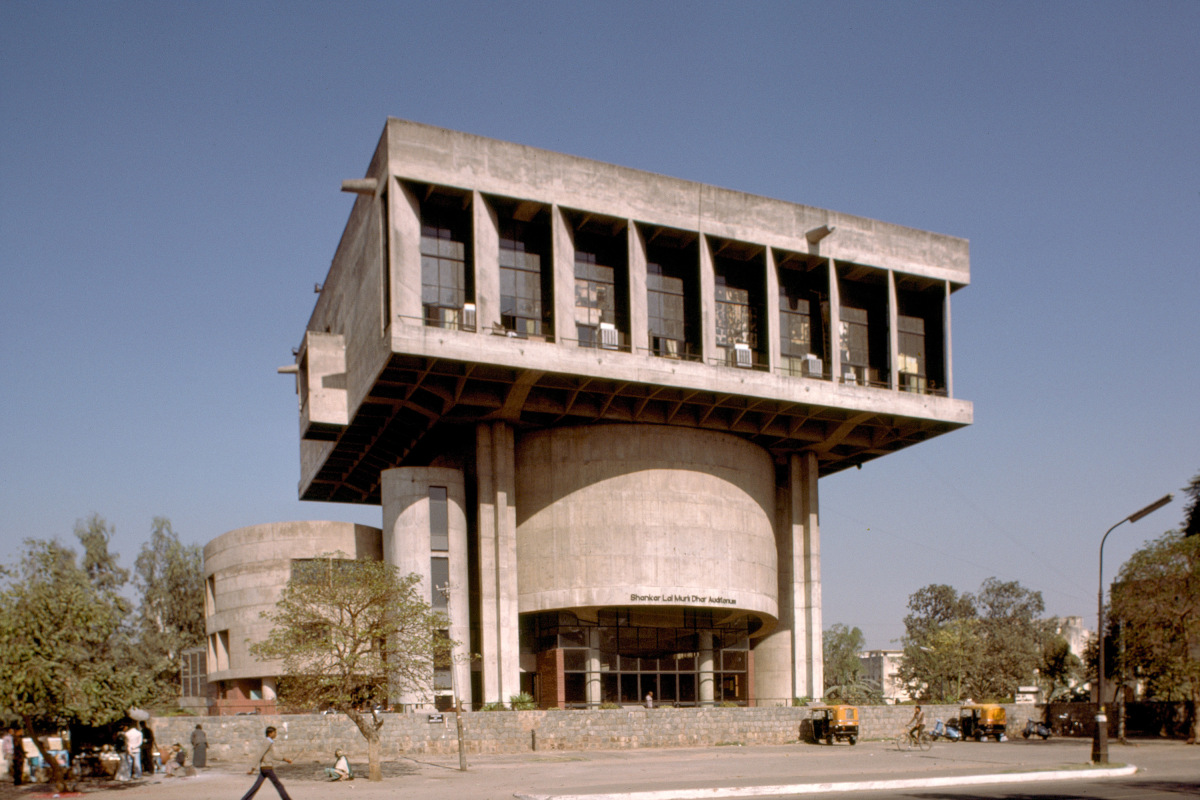

Sri Ram Centre for Art and Culture, New Delhi (Shiv Nath Prasad and Mahendra Raj, 1972).

(2 of 2) Sri Ram Centre for Art and Culture, New Delhi (Shiv Nath Prasad and Mahendra Raj, 1972)