1. They did what human beings looking for freedom, throughout history, have often done. They left.

Stories

Stories

What we are thinking about,

people we’ve met,

what we’re up to.

By Date / A-Z

The Prophet and the Dreamer

(Art)

An exhibition by George Raftopoulos exhibited as part of the Nishi Gallery series, May 2016.

(1 of 3) General by George Raftopoulos.

George Raftopoulos’ latest works play with the notion of the migrant identity or absence thereof. His works are odd things to look at and he knows it. Being an oddity is all part of the migrant experience and for that matter the human one. These paintings are conversations with the past. They don’t tell stories as much as they reacquaint us with people who should never be forgotten. If you enjoy a good landscape then this probably isn’t for you. But then again, maybe it is.

Mostly, when contemporary art looks at a personal story of migration, we’re talking about dodgy photographs and things somebody found in their grandfather’s attic. For me, looking at George’s paintings, it’s all about ghosts on the canvas.

This is a series based around post-war Greek immigration to Australia. George develops these narratives of migration into more than a set of Kodachrome memories.

Post World War Two migration from Greece has become part of our nation’s folklore. This gives almost everything associated with it a mythical quality. From milk bars to fruit shops it’s easy to live in a halcyon era. But there was always more to being Greek in Australia than “Con the Fruiterer’. What is lost in the legend is the often-harsh reality of being a stranger in a strange land.

These works don’t rehash the bare bones of history, but rather explores a parallel emotional story of the lives involved. A key trait throughout the works is George’s own ambition to see Greek immigration to Australia as more than a textbook event. He wants us to remember that the lives often observed through two lines in a government publication or stereotypes in a comedy sketch are those of real people. George’s paintings bring these experiences of the past back into hard currency. They are ghosts of the Charles Dickens kind. Juxtaposed with Greece’s own current crisis of refugees, the series reminds us of the shifting way we see migrants both past and present. George’s art reminds us that all humans are migrants. Travelling between cultures has never been a case of just reaching point B. Whether it be sixty years ago, a million years past or last week, it’s not about the migrant but who they are seen to be that matters.

Via a process of primitively printed smudges on each canvas, George loosens the identity from individual portraits. While we know that these images are based on Greek immigrants, their immediate identification is lost. They could be anyone. Freed of this ethnic bias, we are left with who we are. As a collective group, they look like a gallery of freaks. As individual images you respond to the traits you see in yourself. These are light and dark mirrors, both complimenting and condemning the viewer.

I’m a Gen X, one of the last eras in which the term “wog” was still used as part of everyday speech. Few of us cringed at the term back then, although I do now. But just because something becomes politically incorrect, doesn’t necessarily mean that society has changed or that the wounds have healed.

(2 of 3) Prophet by George Raftopoulos.

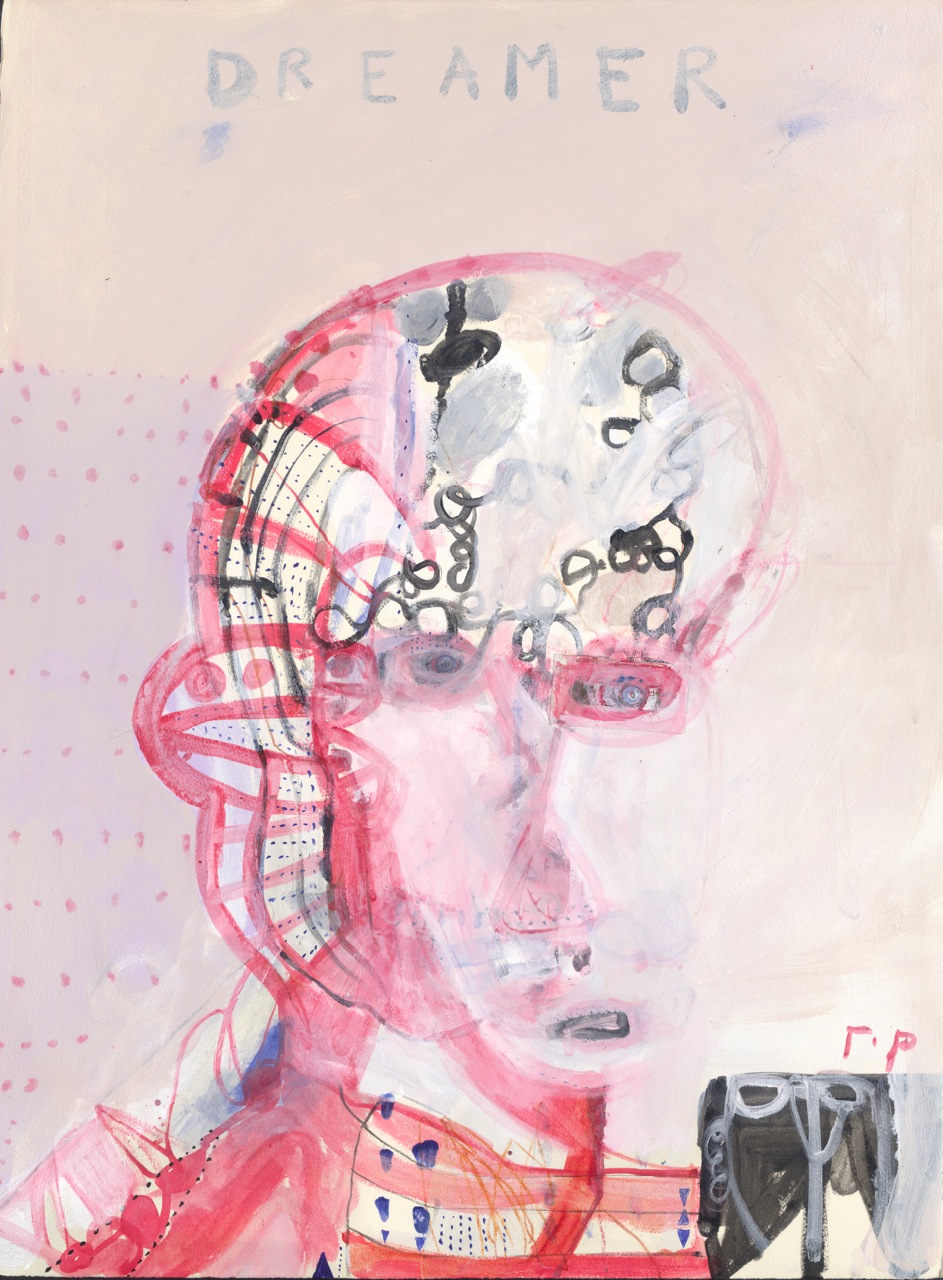

(3 of 3) Dreamer by George Raftopoulos.

The works ‘Prophet’ and ‘Dreamer’ reflect this sense of dystopia. ‘Prophet’ carves a face out of black and white toning. Black to the left, white to the right and grey down the middle. Today, as hordes of Syrian refugees flood Greece, it is a reminder that migrants are seen in a variety of emotive ways, both in hindsight and at the time of their arrival. The work doesn’t make a judgment, the audience does. George overlays the image with a lace like motif, it mimics some kind of medieval costume drama. There is a sense of royalty. Perhaps, as George likes to suggest we are all “emperors” with our new clothes. The way we see fresh arrivals is filtered by our own aspirations for the world. The lace effect across the prophet’s face resembles the fabric you might find at the altar of a local church or a tablecloth from the Grecian cafe of your mind. The identity of the migrant is as much what we project as who they really are.

‘Dreamer’ is a humorous brain piece. The strong fleshy pink colour is at odds with the more austere greys and blues of its brother, the ‘Prophet’. Whilst ‘Prophet’ suggests a John the Baptist style ire, preaching outward to us sinners, in ‘Dreamer’ the audience is literally looking inside the mind of a migrant. As George’s frantic lines in the cranium suggest it is a head filled with both ideas and emotion. An ear pointing in one direction as the face is moving in another, a life in a hurry to start. There is a need for the migrant to keep travelling, whether to arrive at a destination quicker or to avoid being run out of town.