1. They did what human beings looking for freedom, throughout history, have often done. They left.

Stories

Stories

What we are thinking about,people we’ve met,what we’re up to.

By Date / A-Z

Porosity Kabari… Ideas that passed through junk.

(Design)

‘Porosity Kabari’ was an exhibition we presented as part of our Nishi Gallery series in July, 2017.

‘Porosity Kabari’ was an interdisciplinary, cross-cultural, collaborative project between Australian object designer Trent Jansen, artist and architect Richard Goodwin, and Indian design thinker Ishan Khosla.

The trio worked over three weeks to produce furniture and object pieces made from materials and craftsmanship sourced solely from the ‘Chor Bazaar’ (thieves market) and ‘Kabari Bazaars’ (junk markets) in Mumbai, India.

The project was aptly named. Porosity – the ability of a membrane or material to let liquid and gases pass through it; or in this case ideas and people. Kabari – the Hindi work for junk.

The market neighbourhoods within which this project took place are where many of India’s useful objects end up. It is also where they are often given a second life – car panels are transformed into ad-hock cookers and old clothing is quilted into rugs for snake charmers. The designers learnt from conversation and experimentation with the vendors and crafts people working in these manic marketplaces.

The process challenged them to ‘make something from something else’ – the essence of sustainable design. In a society such as India, without many of the common social safeguards that other “more economically developed” nations enjoy, the survival is determined by people’s ability to be creative and resourceful. India is a place where resourcefulness is part of the everyday. On the flip side, developed nations struggle with the environmental implications of designed obsolescence and disposable consumption. This project forced the designers to adopt a human oriented design approach and to make do with what was on hand.

Works by Trent Jansen

For this project Trent Jansen explored the process of jugaad – of doing just enough with what you have on hand and figuring it out as you go. At first it made him a little nervous. In contrast to his usual thoroughly researched projects; and used to working through production processes in a strict and controlled environment; this three week jugaad process was a free fall.

The process was based on observations and reactions – generating ideas by improvising forms based on those that were possible and using the techniques and materials that were readily available. It was also improvised – options and problems were decided upon and solved as solutions came to mind and were therefore also dependant on current mood and state of mind. These reflexive decisions based on availability and mood determined the destiny of each object.

Jansen made a stool, side table and crockery from terracotta, ‘Jugaad with Pottery’, with potter Abbas Galwani; and stools from metal with a small metal workshop, reshaping a car bonnet, copper panels and copper rivets, ‘Jugaad with Car Parts’.

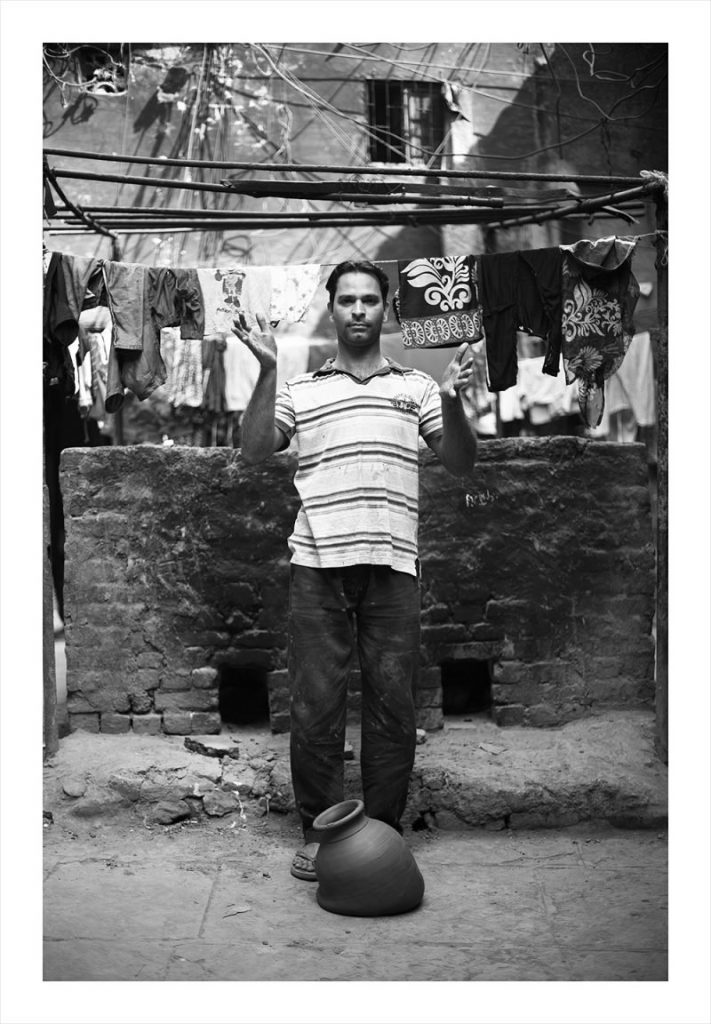

For ‘Dropping a Kubhar Wala Matka’ Jansen payed homage to Ai Wei Wei’s controversial work, ‘Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn’, 1995. In this work, Abbas Galwani, a kumbhar wala (potter) living and working in Dharavi, drops a traditional Indian Matka. With this act, Abbas denounces the cultural structures that restrict his social mobility, impede his ability to gain recognition and respect for his unquestionable skill, and hinder his capacity to provide for his family. The piece is a critique of the traditions and history that underpin Indian social conventions. In India, the kumbhar wala is among the lower castes, meaning that these craftspeople, who make functional objects serving millions of Indians on a daily basis, do not earn the respect that they deserve for their role within Indian society.

(1 of 6) Portrait of Abbas Galwani for 'Dropping A Kumbhar Wala Matka' by Trent Jansen. Shot by Trent Jansen. An homage to Ai Wei Wei’s controversial work, ‘Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn’, 1995.

(2 of 6) 'Dropping A Kumbhar Wala Matka' by Trent Jansen. Shot by Neville Sukhia.

Works by Richard Goodwin

With his ‘Binary Maquettes’ Goodwin explored the ratio of the golden mean (1:√2 – one as to the square root of two) a mathematical ratio found in nature and used in design to create compositions that are in proportion. In ancient Greek philosophy, the golden mean is the desirable middle state between excess and deficiency. With these maquettes Goodwin investigated the current threats to our existence as human beings.

With his installation ‘1-√2 Charpai For Mumbai’ Goodwin combines a motor scooter and an Indian charpai bed. With this high-rise bed on the move he explores where the body ends and architecture begins. He ponders on the lessons that the Mumbai slums can offer for 21st century architecture – by drawing on its highly developed social constructions, the problems there can be continuously addressed by the people that live and work there.

With his ‘Klein Chair’ Goodwin explored his obsession with the Klein bottle – in mathematics, an impossible vessel that swallows itself, it has no inside or outside.

(3 of 6) '1-√2 Charpai For Mumbai' by Richard Goodwin. Shot by Neville Sukhia.

(4 of 6) 'Klein Chair' by Richard Goodwin. Shot by Neville Sukhia.

Works by Ishan Khosla

Khosla’s works meditated on his contemporary India.

‘Construct:Deconstruct’ was a collection of furniture made from found objects and pieces of wood scavenged from the streets of Mumbai. It references the cycle of material use and reuse (and further reuse) in India. These naïve objects don’t follow any design principles, choosing instead to emulate or force gestures – for example a stool that forces the sitter to prop one of their feet up (a common sitting pose in India).

‘Partition of the Mind’ represented the division between idealised “progress” and the economy in India versus traditional values and ideals of egalitarianism. With everyday domestic objects – brass thali, lassi glasses and tifins; Khosla spoke of the endless cycle of consumerism and desire in his globalised India and the increase in the divide between those with plenty and those with nothing.

(5 of 6) 'Construct:Deconstruct' by Ishan Khosla. Shot by Neville Sukhia.

(6 of 6) 'Partition of the Mind' by Ishan Khosla. Shot by Neville Sukhia.